In Color, on the Land

by Matt Wycoff

Cy Gavin, Underneath the George Washington Bridge (detail), 2016.

© Cy Gavin, courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown's enterprise, New York/Rome

The exhibition Young, Gifted, and Black: The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art is curated from the private collection of art patrons Bernard I. Lumpkin and Carmine D. Boccuzzi. The selections made highlight an emerging generation of black artists engaging the work of their predecessors, while also mining new, and in many instances more colorful, vocabularies of symbolism. Over the past ten years, the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi family has assembled a wide range of art, in all mediums, from roughly two generations of black artists. The older generation of artists represented in the exhibition is presented as both lineage and foil for the younger; while the younger generation is presented as the fruit of the older generation’s struggle for equal representation. The earliest examples on view date to the mid-1990s, while many from the younger generation were made after 2012 and are among the artists’ first professional offerings.

Addressing black identity and history through use of the color black has been a major concern of both generations represented in the exhibition; as if by eschewing mahogany, raw umber, and burnt sienna, they might render (and take ownership of) a depiction of blackness as it exists inside the racist mind—monolithic, impenetrable, and terrifying. Attempts to own the meaning of the color black can be seen as early as 1903 in W. E. B. Du Bois’s seminal collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, and was perhaps most popularly expressed in James Brown’s funk anthem “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” released in 1968. Masters of this approach in contemporary visual art, such as Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker, have likewise been trailblazers in the radical transformation of the associative link between the color black and the African American experience. It is through this process of reclamation that black artists, musicians, writers, and thinkers have transformed the meaning of the word black in the nomenclature.

Bethany Collins, Too White To Be Black, 2014. © Bethany Collins, courtesy Patron Gallery, Chicago

The way the color black came to represent the many-hued African diaspora begins with slave owners and traffickers distancing themselves from the property and product of their trade. The owners and traffickers being white, black served as an expedient antonym for the symbolic distortion of enslaved individuals into something less than human. It’s a history no adjective seems to meaningfully illuminate. Maddening, infuriating, atrocious, and staggering all fail to describe the four hundred years of terror and denigration that indelibly linked people of African origin to the color black and its attendant symbolisms that have included, but are by no means limited to, stupidity, laziness, the devil, and an absence of visible light. (i)

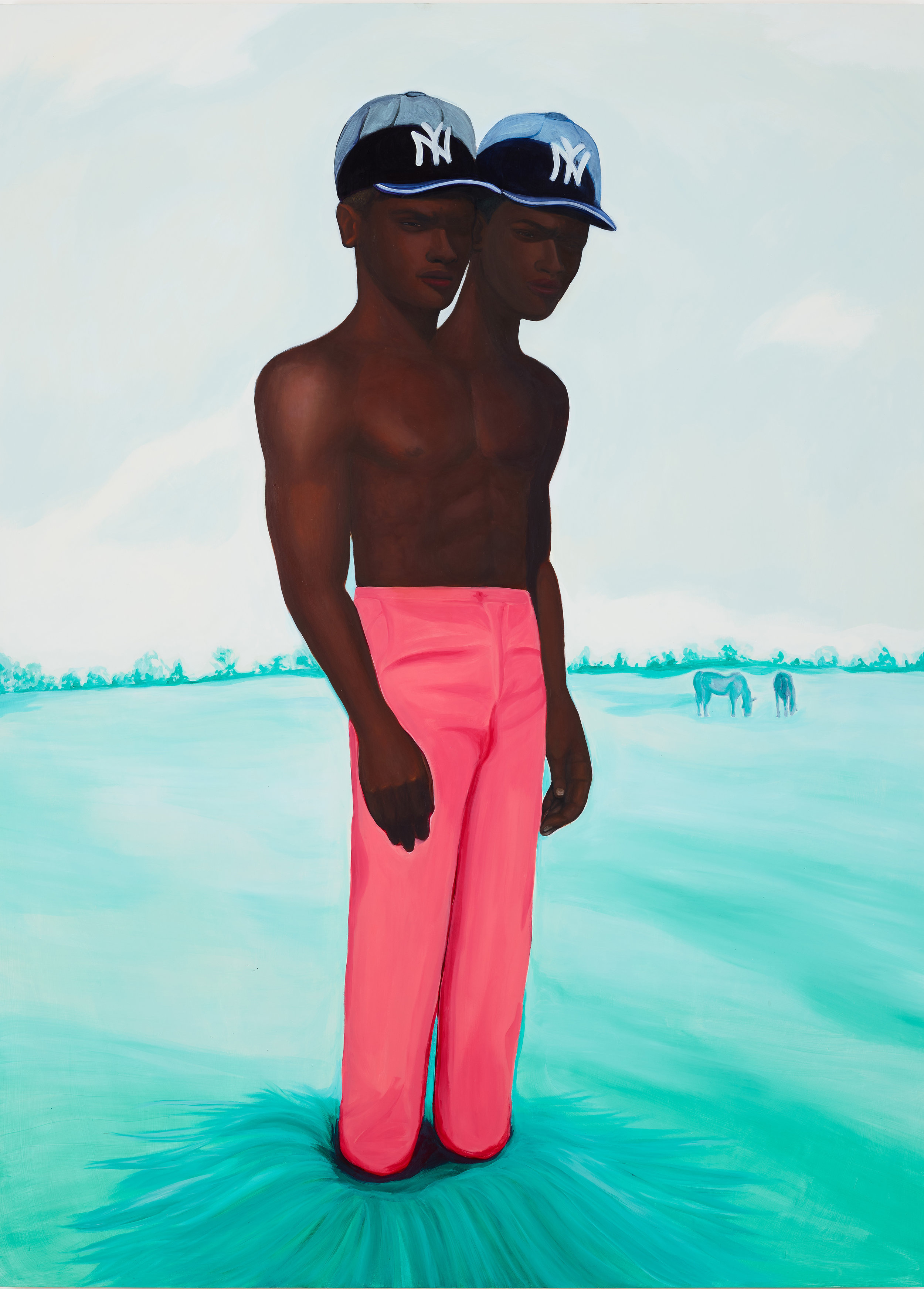

Hard-earned reclamation of the color black dramatically underlines one of the most striking visual shifts presented in Young, Gifted, and Black: a riotous and radical explosion of color, primarily among the younger painters, to represent the human form. Jordan Casteel shifts skin tones to shades of moody cobalt. Christina Quarles drapes bodies like Dalí’s clocks, while denoting skin color in ribbons of orange sherbet, peach, and midnight blue. Arcmanoro Niles renders blackness in rose (think Afros of glittering pink). And Vaughn Spann paints a lurid, Day-Glo, floral tapestry and a shirtless, two-headed man in a teal landscape donning hot-pink trousers and matching Yankees caps, one for each head. There is a jarring contrast in the exhibition between these radically colorful works and those that are primarily black. Their separation into colored and black groupings initially feels crude and oversimplified. Claudia Rankine’s raw refrain, “What did you say?” feels apt, if only for an instant, before the switch from black to color gives way to a sense of embarkation. (ii)

Taken together, these new, sensationally colored works invoke surrealist and psychedelic visual histories to tackle issues of race and identity, but one doesn’t catch a whiff of the defiant 1960s proclamation to “turn on, tune in, drop out.” The work is about being in, not dropping out. Needless to say, dropping out of the mainstream is a much less appealing prospect to someone who has been systematically barred from entry. From this view, the celebration of drug culture itself can be seen as indicative of privilege. The absence of drugs and dropping out amid the use of psychedelic imagery points to a lineage of black thinkers, such as Malcolm X, who have railed against drugs and alcohol as tools of the oppressors. (iii) But what is psychedelia without the drugs?

D'Angelo Lovell Williams, The Lovers, 2017. Pigment print/ 20 x 30 in. © D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Courtesy of the artist and Higher Pictures

The surrealist and psychedelic imagery on view represents a dramatic reworking of visual histories that updates twentieth-century responses to rapid social change, shifts in moral and ethical boundaries, and expanding notions of identity. D’Angelo Lovell Williams’s photograph The Lovers (2017) reimagines René Magritte’s 1928 surrealist painting with two black men veiled in do-rags locked in a kiss, Allison Janae Hamilton’s Untitled (Three Fencing Masks) (2017) transforms fencing masks into uncanny personal totems, and Jacolby Satterwhite’s video animation Reifying Desire 5 (2013) constructs a queer, psychological dreamscape. Perhaps the intoxicant for the younger generation represented here is access to new and wider audiences in the art market, rather than drugs, and the effect is exhilarating.

The artists represented in Young, Gifted, and Black are also bringing this informed, expressive sensibility to representations of nature. Cy Gavin’s paintings call to mind the psychedelic in his use of color–roiling landscapes streaked with saturated primary colors (red, yellow, blue) and electric secondary colors (orange, purple, green). But his surging seas, skies, and archipelagos are also filtered though the graffiti-culture language of walls streaked with oversprayed burners. Here, there is an opposition to the history of landscape painting that romanticizes the idea of nature: the land literally feels overwritten. Gavin’s landscapes pry open a space between the idea of nature and the often-bloody and contested land itself, making room for histories of racial inequality. This space is haunted by a history in which enslaved individuals were property, treated no different legally than the land. But other histories, such as the disproportionate impact of climate change on communities of color, quickly crowd the void as well. With a sensibility of striving, songful, brainy lamentation, Gavin’s landscapes demand accounting for these and other histories of inequality.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Blue Dancer (detail), 2017.

© Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

Of the artists represented here, Gavin confronts the landscape most directly and consistently, but one also catches fresh approaches to nature and the landscape in the paintings of Quarles, Caitlin Cherry, Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Jennifer Packer, and, I might argue, the installations of Eric N. Mack. Not to mention the volumes that should be written on Clifford Owens’s self-portrait as a recumbent, hands-up-don’t-shoot, neutered (tucked) nude amid a verdant green, pastoral landscape. Elizabeth Alexander’s poem “American Sublime” might fit to key the many representations of nature on view in the exhibition. Alexander’s “violent sunshine,” “gentle luminosity,” and “vast, craggy, un- / domesticated” landscapes occur entirely in parentheses. (iv)

Young, Gifted, and Black also features a wide range of portraiture, including painting (Lynette Yiadom-Boakye), sculpture (Lonnie Holley), collage (Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle), mixed-media (Troy Michie), and photography (LaToya Ruby Frazier). The invention of photography, in 1839, marked a radical turning point in the history of portraiture and is a fundamental frame of reference for all the works of portraiture on view. Photography not only created a new, more accessible and expedient medium in which to represent individuals, but it also challenged artists in traditional mediums, such as painting and sculpture, to profoundly reimagine how, and with new urgency why, they represent the human form. In the 180 years since photography appeared on the scene, ideas about what constitutes a portrait continue to expand. It is in this spirit that a text-based work, such as Sadie Barnette’s Untitled (People's World) (2018), which alters pages from the FBI’s file on her father as an act of artistic reclamation, is included as an example of conceptual or nontraditional portraiture.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Dark Room Mirror Study (0x5A1531), 2017. © Paul Mpagi Sepuya, courtesy the artist and team (gallery, inc.), New York

The works of portraiture selected for the exhibition also demonstrate the many ways contemporary black artists shape, and reshape, the black experience through figurative representation. In doing so, they further the concerns of a lineage of portraiture that spans from the portraits of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, to the studio photography of James VanDerZee, to the pioneering photojournalism of Gordon Parks. In Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s Dark Room Mirror Study (0x5A1531) (2017), for example, the artist questions the relative absence of representations of gay men of color in the photographic record by making visual reference to the early history of studio photography. While the striking choreographed poses of the trio of black women in Deana Lawson’s Three Women (2013) are reminiscent of backup singers, Lawson has their vulnerability and power command center stage. And Gerald Sheffield’s kbr contractor (Iraq 2007) (2018) points to potential futures of representation across perceived racial barriers. These works display a spectrum of approaches to portraiture that includes direct figurative representation, works that question histories of mis- and underrepresentation, and those that expand notions of what constitutes a portrait.

And then there’s the mask, which traverses notions of identity, history, and the land at a clip. The dizzying array of masks created on the African continent is tied to the land by centuries of use in ceremonies that accompany planting, harvesting, birth, and death. These masks seem to get at the root of all human emotions, while somehow maintaining a fearsome understanding that everything is subject to the earth. Use of costume and the mask in the work of black artists has long addressed lost relationships to ancestral homelands and has become a deeply symbolic well of meaning for black heritage and identity. A short list of mask imagery represented in the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection includes: mannequin as mask (Narcissister), buttons as mask (Lonnie Holley), scribbles as mask (Rashid Johnson), plastic garbage bag as mask (William Pope.L), rock salt as mask (Felandus Thames), Ellsworth Kelly as mask (William Villalongo), do-rag as mask (D’Angelo Lovell Williams), brick wall as mask (Derrick Adams), fencing mask as mask (Allison Janae Hamilton), and, perhaps the most revelatory, the camera lens as mask in Sepuya’s smart, historically savvy seductions. This flux and reinvention is not unlike an aspect of the Internet in which new terms are created to describe what is essentially very old human behavior, for example: ally theater, sucked into a follow, Twar, vaguebooking, finsta, and nontroversy. Young, Gifted, and Black presents similarly updated (sometimes pithy, often profound) takes on the ancient arts of costume and the mask.

William Villalongo, Sista Ancesta (E. Kelley/D.R. of Congo, Pende), 2012. © Villalongo Studio LLC and Susan Inglett Gallery, New York

Symbols do change meaning, after all. As with the color black, shifts in our use of symbols often require a concerted effort, although circumstantial and historical forces are also at work. Two points give important context to the exhibition: the sustained efforts of liberals to be good amid the political right’s flirtation with totalitarianism and the golly-gee insanity of an art market fueled by gigantic accumulations of private wealth. Amid these forces’ ebb and flow, there is perhaps more of a sense now, a belief even, that social change can occur, is in fact occurring, through the wiles of the art market. For many, there is a near-constant back-and-forth between a firm belief that art can and does make change, and a question of to what extent it should overtly try. Many of the artists in Young, Gifted, and Black are at the very heart of this debate. It raises a question central to the exhibition: Can one look at the work of this emerging generation of black artists without the lens of identity politics?

One answer to that question is rooted in Du Bois’s concept of “double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” (v) Given this perspective, one might say that black artists have largely been denied the opportunity to choose whether their work is political or not. Artists in the exhibition, such as LaToya Ruby Frazier, Jordan Casteel, and Chiffon Thomas, present subjects whose very matter-of-factness affirms their rightness on the scene, while at the same time raising questions of identity politics. The persistence of identity politics in the work of these artists is an issue of historical circumstance, but it is also, and importantly, one of intent.

Vaughn Spann, Staring back at you, rooted and unwavering, 2018. © Vaughn Spann, courtesy Martin Parsekian / Half Gallery

Through their reworking of the color black, psychedelia, landscape, nature, portraiture, and the mask, the artists featured in Young, Gifted, and Black are finding deft new ways to address the history and meaning of blackness. They are also pointing to the fact that a true equity in seeing and being seen seems to be the clearest way out of the racial paradox that exists in the United States and elsewhere. We can view the work of black artists as being about asserting black identity and representing lived experience. (Consider the difference between the two.) Staring at Vaughn Spann’s Staring back at you, rooted and unwavering (2018) feels almost like a game of stack hands, in which the contest of seeing and being seen vie for the top. In Toni Morrison’s famous framing of the “process of entering what one is estranged from,” she writes, “imagining is not merely looking or looking at; nor is it taking oneself intact into the other. It is, for the purpose of the work, becoming.” (vi) To see and be seen in this way requires an emotional openness, but also a firm intellectual position. The feet of Spann’s two-headed man, anyway, are planted firmly in the earth.

For the past ten years, Matt Wycoff has worked as collection curator for the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection. Wycoff is also an artist, woodworker, and writer living in Brooklyn and Stephentown, New York. His work can be seen at mattwycoff.com.

References:

(i) For an example of how blacks have been likened to the devil, see James Baldwin, “Stranger in the Village,” in Notes of a Native Son (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955), 178.

(ii) Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014), 43.

(iii) See the 1964 speech at the founding rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity in Malcolm X, By Any Means Necessary (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1992), 76-78.

(iv) Elizabeth Alexander, American Sublime (Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2005), 89.

(v) W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903, repr., Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1994), 2.

(vi) Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (New York: Vintage Books, 1993),